Hughie Woolford

20231217

Hughie Woolford was one of the circle of Black Baltimore musicians born in the 1880s who went to New York in the 1910s and spent the rest of their career in the NY metropolitan area. The most famous of these, of course, was Eubie Blake. Garvin Bushell told Nat Hentoff ("Jazz Panorama", ed. by Martin Williams, 1964, pp. 84-85) "Baltimore had a great variety of jazz and many excellent performers. They came to New York in droves, and a large proportion of the significant figures in early New York jazz turn out to have come from Baltimore or near by. There were pianists Eubie Blake, Edgar Dow[ell], Bobby Lee, John Mitchell, banjo, Jerry Glasgow, clarinet, etc. Chick Webb later came out of Baltimore . . . Their jazz was based on ragtime piano practices, and piano ragtime influenced the way they played their horns."

Woolford was born March 26, 1885 (according to his WWI and WWII draft registrations, and the month and year given in the 1900 census) in Baltimore. By as early as 1904 he is listed in the Baltimore city directory as a musician. He was remembered many years later by Eubie in interviews as one of his piano-playing "competitors" in Baltimore, along with Edgar Dowell. The 1908 Baltimore city directory fascinatingly lists all three: Hubert Blake, 1505 Jefferson, musician, Edgar Dowell, 106 May St., musician - the two addresses near the Johns Hopkins Hospital are only a 5-minute walk apart - and Woolford, musician, at 436 Regester St., about 0.9 mi to the south of Dowell and Blake's home addresses. (The Baltimore city directories of this period mark listings of Black individuals with an asterisk, which helps further strengthen the case that these musicians are indeed the ones we are concerned with.)

The reason that researchers have heretofore apparently not found the early documentation of Woolford's life is that we all assumed "Hughie", sometimes rendered as "Hughe" or just "Hugh", were all versions or nicknames for "Hugh". In fact, Woolford's given name turns out to have been "Eugene", and that is how he is listed in all the early documentation in Baltimore (censuses and directory listings.)

The

last time we find Eugene Woolford in the Baltimore city directory is in 1911,

which is consistent with the fact that of the Clef Club concerts in 1910, 1912,

and 1914,

"Hugh Woolford" appears as a pianist in the listing of the musicians

in the New York Age articles describing the latter two concerts. Hence we can

assume Woolford has moved from Baltimore to NY around 1911 or early in 1912.

[Note that Eubie is listed in the 1912 Baltimore directory as "Jas.

Blake" (his full name was James Hubert Blake) at 1529 Monument, so he has

not yet made the move to NYC.] The Baltimore Afro-American of Dec. 21, 1912 ran

an item on page 8: "Miss Mamie V. Woolford has returned from New York

where she spent ten days as the guest of her cousin, Mr. Hugh Woolford,

formerly of this city." Lester A. Walton's review of the 1912 concert (May

30, 1912 issue) indicates that the Clef Club orchestra played a piece entitled

"Dance of the Marionettes" by Woolford and the veteran composer Will

Tyers.

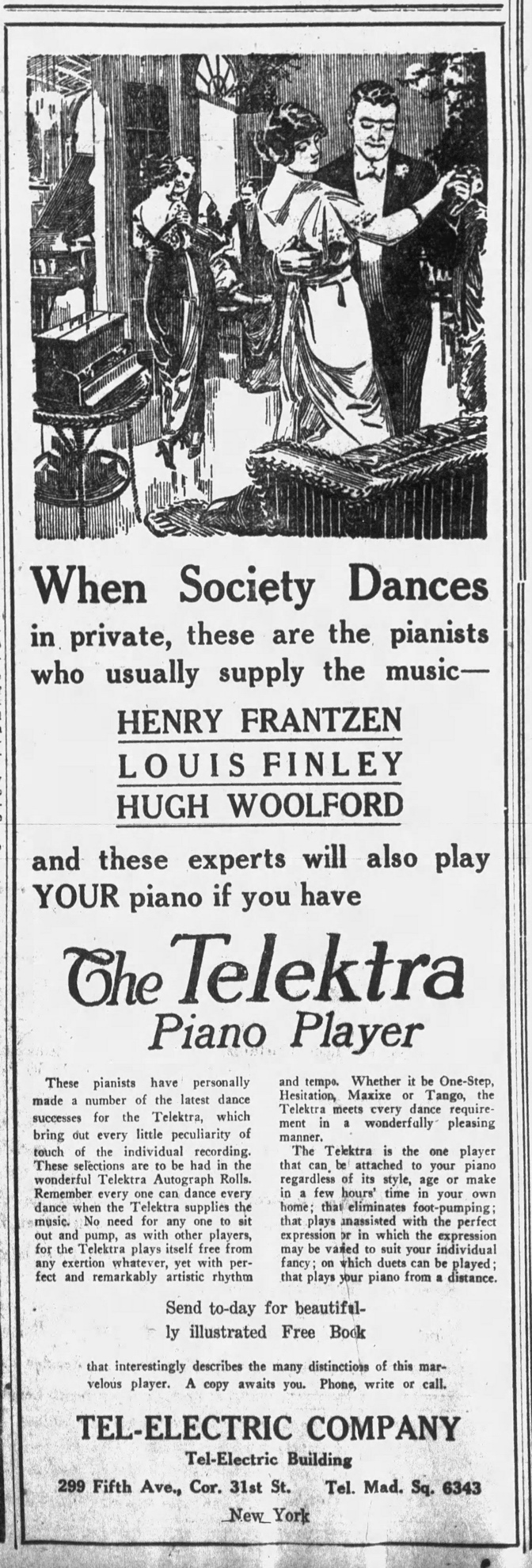

Woolford was evidently well-enough known as a pianist for dances by 1914 that the Tel-Electric company engaged him to make rolls for their Telektra system, as evidenced by the large display ad shown here, from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of January 11, 1914. A sales point is made of the fact that the all-electric system meant that the piano would play without anyone having to pump it, so everyone could dance. Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the three pianists listed in the ad is that two of the three were Black members of the Clef Club (Woolford and Louis Finley). This serves as a reminder of how Vernon and Irene Castles' success in popularizing the then-modern dances with an orchestra of Clef Club members accompanying them had rendered Black musicians very much in demand in society circles in New York by 1914.

Woolford went onto a long career as a musician and singer-entertainer as well as a booking agent in the New York metro area, as evidenced by many newspaper items, including many mentions in stories about social events for which Woolford was engaged to provide music, advertisements for ensembles led by Woolford, and in the 1920s, radio listings for Woolford filling a fifteen-minute slot with "jazz piano".

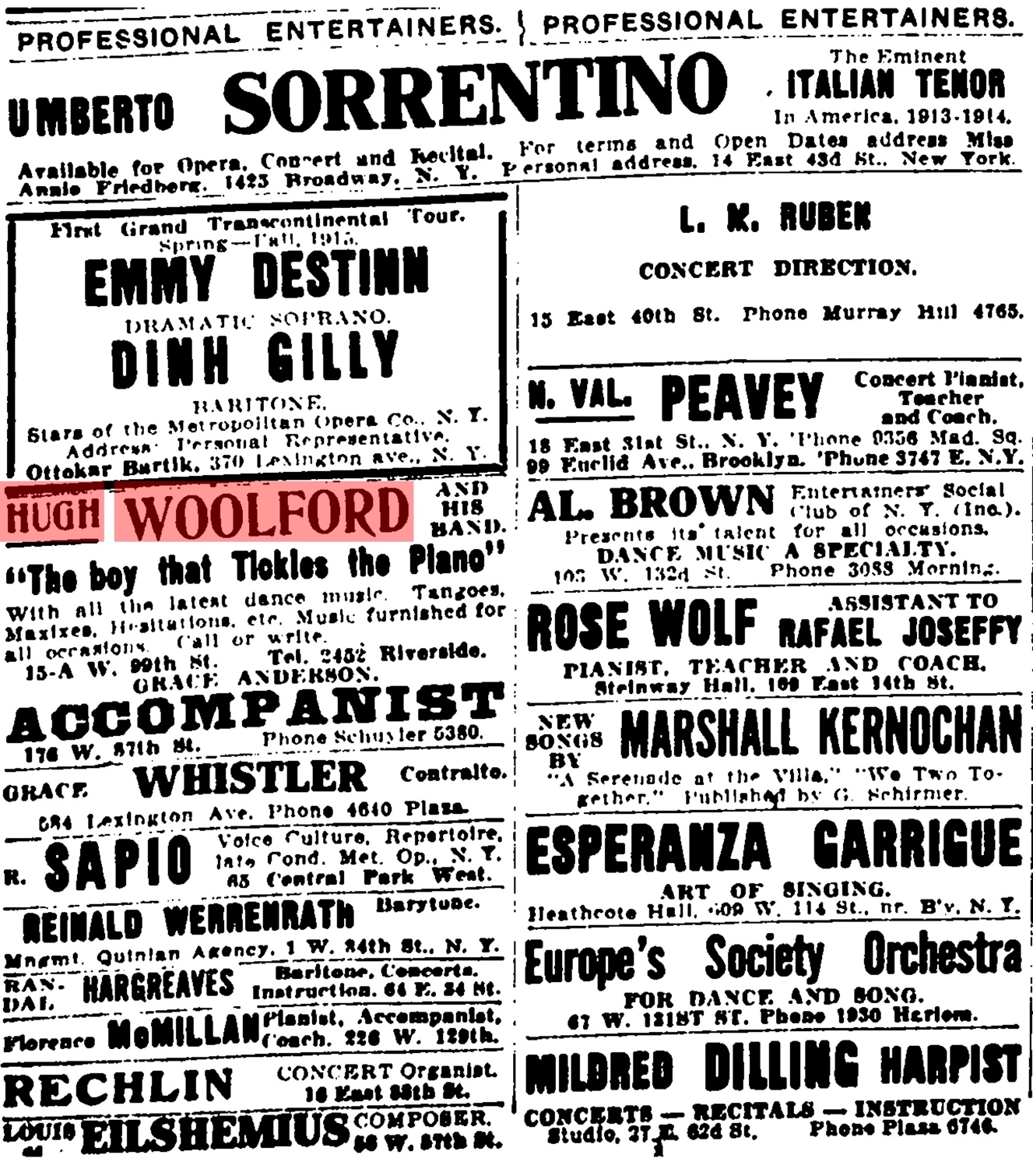

Here is an early advertisement for Woolford's band, from the New York Tribune, May 4, 1914, p. C5. Note the separate listing for Europe's band (by this time, Europe had left the Clef Club and started a new organization called The Tempo Club.)

Woolford composed the music for songs with lyrics by the young Andy Razaf in 1922 for the latest version of a series of shows entitled "Joe Hurtig's Social Maids", according to David Jasen and Gene Jones ("Spreadin' Rhythm Around", p. 205). One of these songs was published by Remick, "My Waltz Divine", copyright registered October 29, 1923. Another copyright of music by Woolford was registered by Triangle Music on December 3, 1921, for an unpublished song with lyrics by Richard Banks entitled "I'm Tired of Living All Alone".

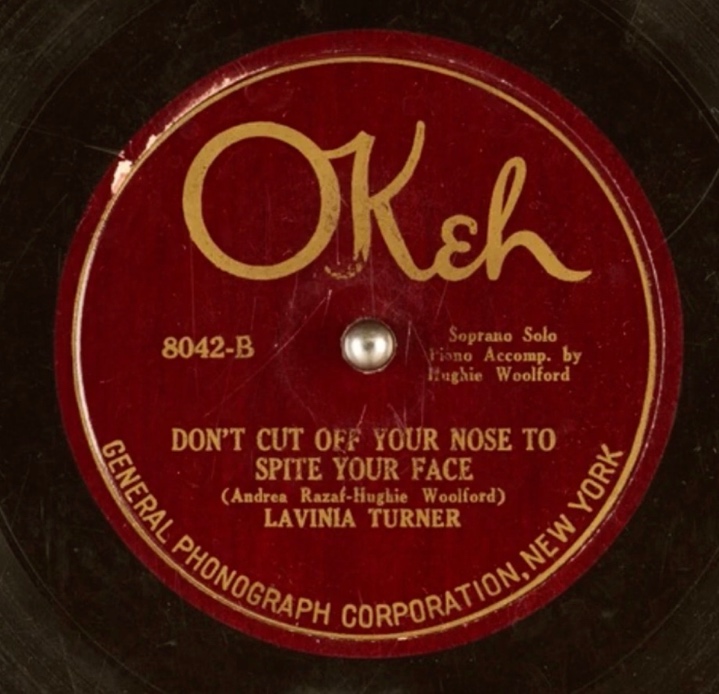

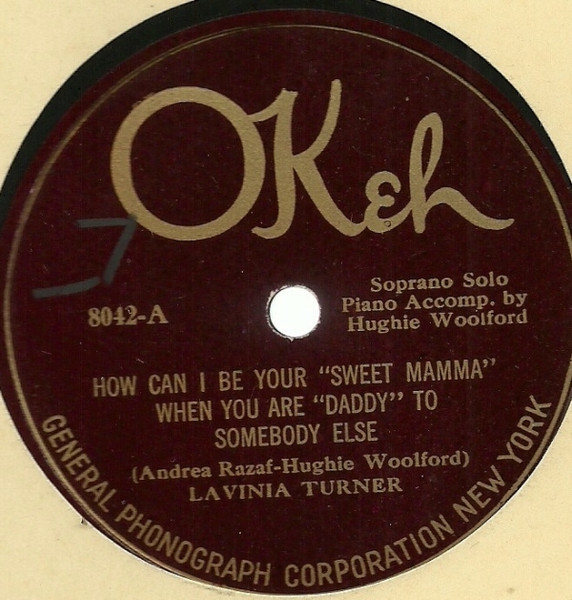

Razaf and Woolford get composer credits on the label of OKeh 8042-A and -B, a record by the classic blues singer Lavinia Turner of "How Can I Be Your 'Sweet Mama' When You're 'Daddy' To Somebody Else", backed with "Don't Cut Off Your Nose To Spite Your Face", though no copyright registration for either song has been located. These sides, recorded in late October 1922 according to Rust, are the only known phonograph records of Woolford's piano playing, for which he is credited on the labels.

The New York Amsterdam News ran a feature about Woolford's career on 25 September 1937, p. 6, with a photo. The address mentioned in the last line was a typo - actually 538 Lenox Ave.

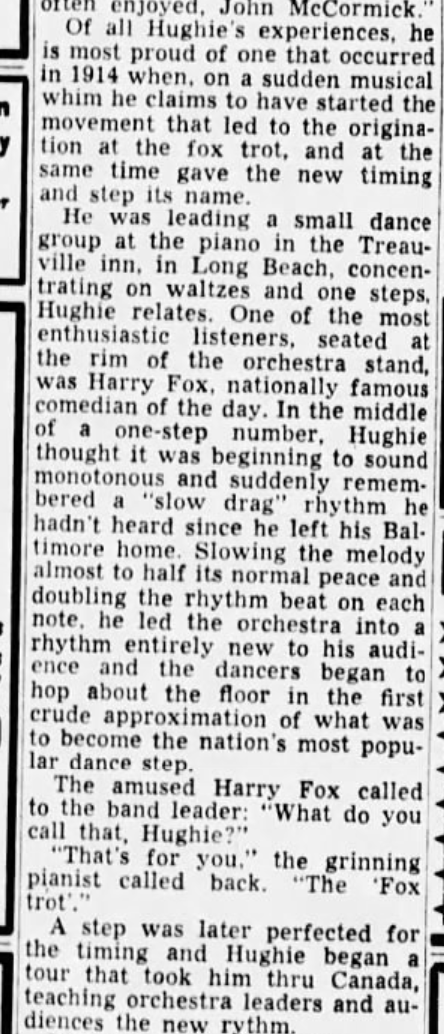

For the rest of Woolford's career, he seemed to have cited his role in the invention of the fox trot from 1914 as a memorable highlight. He told a reporter from the Asbury Park (NJ) Press (August 18, 1946), nine years later, the story, almost word-for-word the same story he had told in 1937:

Woolford's story of the origin of the fox trot is to be compared with the story of Jim Europe playing Handy's "Memphis Blues" slowly and swingingly for the Castles, who adapted what they always said had been an old "Negro" dance into what became known as the fox trot, also supposedly in 1914. (See Reid Badger, "A Life In Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe", pp. 115-117. The way that W.C. Handy told the story in his autobiography "Father of The Blues" on p. 226 it seems clear that the source of the story was Noble Sissle, who was not present in Europe's organization in 1914, so Sissle must in turn have heard it from Europe once he and Eubie became Europe's close associates in 1916.) What is verifiable about Woolford's story is that his composition "The Trouville Canter" was copyrighted and published in September 1914, while an earlier version was arranged by Will Vodery and copyrighted as an unpublished composition under the title "The Woolford Canter" on July 23, 1914.

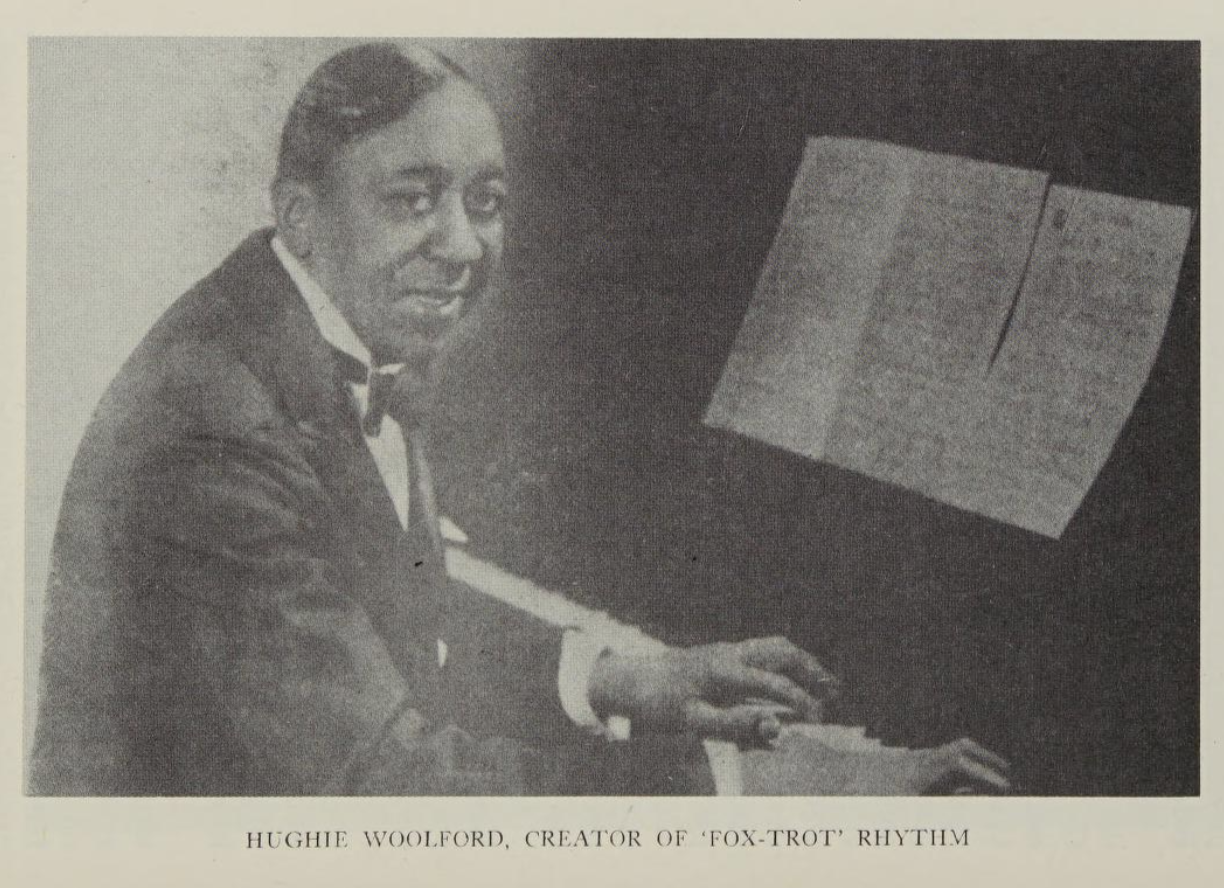

A very similar version of Woolford's story appears in Tom Fletcher's book "100 Years of the Negro in Show Business" (1954), but this cannot be considered in any way an independent verification of the story, because Fletcher writes explicitly on p. 163 of his book "This story was told to me by Hughie Woolford". However, Fletcher does us the service of providing a photo of Hughie:

It appears from the New York City death index that Hughie Woolford died there on 11 June 1958. His widow Katie Barnett Woolford died in Manhattan on 14 February 1965.

Notes on the origin of the fox trot

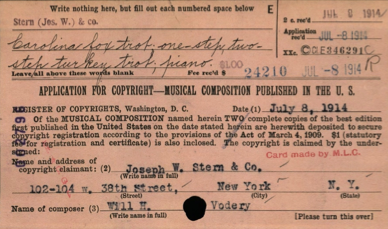

Dance historians have diligently searched for the earliest mention of the fox trot as a dance, and at present, nothing earlier than about mid-July 1914 has been found in newspapers. The earliest reference appears to credit Billy Kent and Jeannette Warner as the originators of the dance (neither Harry Fox nor the Castles), as in The New York Clipper, 18 July 1914, p. 14. In the same mention, Will Vodery's "Carolina Fox Trot" was mentioned as having been composed for Kent and Warner to accompany the dance. Indeed, when Carolina Fox Trot was published by Joseph Stern, on July 8, 1914, its cover features fanciful artwork with Kent and Warner pictured wearing fox ear caps being gazed on approvingly by a fox. The subtitle is "New Society Dance; Originated by Billy Kent & Jeanette Warner; America's Classiest Dancers." Looking at the composition "Carolina Fox Trot" itself, it seems rather indistinguishable from an imaginative piano rag of its time, and the arrangement (by Will Vodery, credited on the publication) is as a rag in 2/4 time without a great deal of dotted rhythms. Furthermore, the subtitle on the first page of the music is "New One-Step". The tempo indication is "Real Slow Drag", leading to the inference that the piece can be played as a fox-trot by slowing it down from the standard march-tempo one-step feel. The copyright registration application for the piece, shown here,

uses the catch-all subtitle "one-step, two-step, turkey trot", perhaps indicating that the piece can be used for different dances by modifying the tempo and the style.

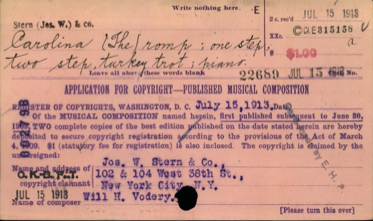

Almost exactly one year earlier, Stern had published an instrumental by Vodery with a very similar title: "The Carolina Romp", subtitled exactly the same way. Its copyright registration card:

"The Carolina Romp" has not been available for examination and comparison with "Carolina Fox Trot", but Peter M. Lefferts's work "Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of Will Vodery: Materials for a Biography" (2016) claims that the two pieces are not identical. Presumably Lefferts has seen "The Carolina Romp". If, despite that claim, the two pieces were to be similar, it might explain why the 1914 piece does not share the stereotypical fox-trot characteristics - rather, it might be a relabeling to take advantage of the sudden demand for music to accompany the dance by the artists portrayed on the cover and cited for the invention of the fox trot.

It is indisputable that the fox trot is suddenly mentioned frequently in the New York papers starting in mid-July 1914 and the frequency of references shoots up in the autumn of that year. References a little later in the year in newspapers outside New York generally identify the fox trot as a craze that started in New York.

Examining the Catalog of Copyright Entries for 1914 (Music) shows not a single reference to "fox trot" in the first half of the year. The earliest mention I have seen of "fox trot" appears on July 8, and it is the aforementioned "Carolina Fox Trot". The next oldest reference is "Meadowbrook Fox Trot" on July 20, and this piece by Arthur M. Kraus, like "Carolina" published by Joseph Stern, seems much more in line with the kind of bucolic, soft-shoe feel that seems to be associated with the fox trot. The recording from September 1914 by the Victor Military Band (see Library of Congress website) is played at a normal fox-trot tempo of 90 half notes per minute (in 4/4 time), distinctly slower than one-step tempo (more like 120 half notes per minute). Two more pieces identified as fox trots are copyrighted in August: the fox trot version of Chris Smith's song "Ballin' the Jack" (yet again published by Stern) with an extra strain by James Reese Europe to make it a three-strain piece on August 7 - with an inset photo of Billy Kent and Jeanette Warner, subtitled "Creators of the 'Fox-Trot'", at least on the edition in my collection, leading to the idea that Stern's official creator of the fox-trot was Kent and Warner. The second August fox-trot was "Reuben Fox Trot" by Ed. Claypoole (inevitably, another Stern publication.)

The number of fox-trot publications found for September is four (including Woolford's "Trouville Canter" identified as a fox trot - note that the unpublished version of July as "Woolford Canter" is not identified in the copyright application as a fox trot), but October has 14 more. The October 1914 fox-trots include two from composers of continuing interest today: Stern's publications of Eubie Blake's "The Chevy Chase" - Blake's first published composition - and Luckey Roberts's "Palm Beach". I stopped counting at that point - the number for November is considerably larger.